This has been a rare year where each of the 15 Tests played so far have yielded results, 11 of them in four days, three within three days and the New Year’s Test involving India at Cape Town producing the shortest completed match ever-lasting 656 balls across just two days.

It can’t be coincidental that this year has also witnessed India’s biggest ever Test win, or that this decade has already produced three of the 10 shortest ever completed Test matches, none of the other seven coming after 1935. In short, Test cricket is becoming shorter, and draws are going out of fashion at breakneck speed.

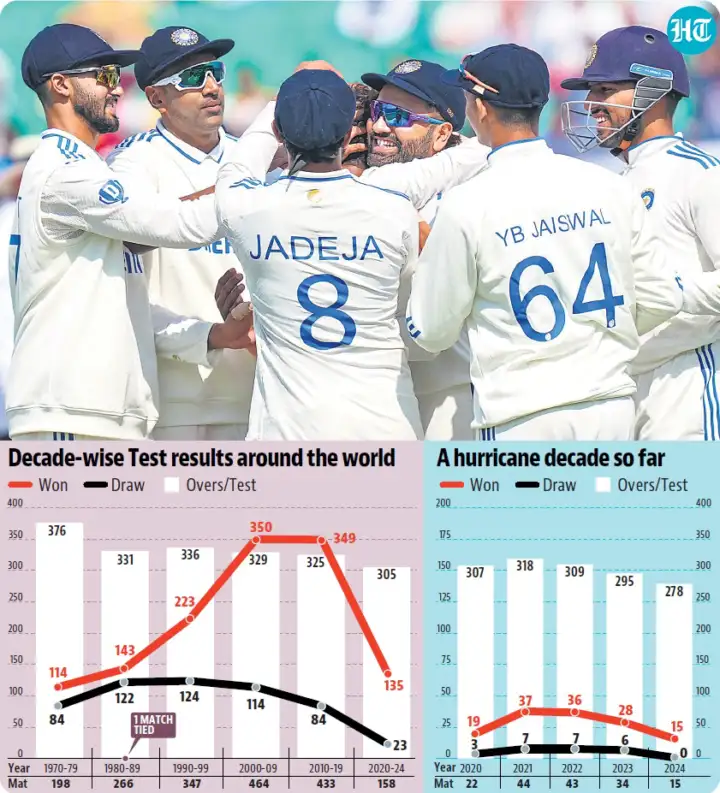

The slide wasn’t exactly drastic till this decade. Traditional form of cricket had largely gone untouched till the 1970s when the one-day format started gaining more traction with two World Cup editions. Still, the average duration of Test matches during this decade was 376 overs, translating to just over four days of cricket. It was only in the 1980s that the influence of one-dayers became markedly visible, with the average duration decreasing to 331 overs per Test, a change also probably brought upon by the increasing tours of the subcontinent where spinners could run through sides within sessions.

That the average duration of Tests didn’t fluctuate much through the next three decades-336 overs in the 90s, 329 overs in the 2000s and 325 overs in the 2010s-can be more or less attributed to the emergence of some of the finest ever Test batters who could hold forte against great fast bowlers and spinners on even the most devious of pitches. This was also perhaps the most balanced phase in the history of the game, witnessing the emergence of a strong post-Apartheid South Africa, the slow disintegration of West Indies, Australia putting together two of the greatest winning streaks ever, Sri Lanka and New Zealand building an enviable home record, Pakistan beginning to win more consistently in England, and India expanding on their home invincibility by registering series wins in England and Australia.

But no decade has seen as much result-oriented cricket as the 2020s, with the result percentage scaling an all-time high of 85.44% from 57.57% in the 1970s. The overs required for the shortest match in every decade has also dropped significantly-from 194 in the 70s to 174 in the 80s, 164 in the 90s, 148 in the 2000s, 152 in the 2010s before nosediving to just 107 overs at Cape Town earlier this year.

Compelling too is the sharp decline in average duration of games-from 325 overs in the 2010s to 305 since 2020. But more astonishing is the slipping average game time in the last two years-295 overs in 2023 and 278 overs this year that is yet to witness a draw. Considering 90 overs are bowled per day, these are game averages of over three days but barely into the second session of the fourth day in Test cricket, once again highlighting the increasing redundancy of the fifth day.

Four-day Tests have been part of the conversation for some time now, not only because the ICC has trialled it but also because of the overwhelming majority of games organically finishing so quickly in the last few years. Addition of newer sides like Ireland and Afghanistan has played its part in knocking off a few overs from the average Test duration but to be fair to them, many hard-fought games between well-matched sides have also ended inside four days.

T20-influenced batting has often been pointed out as the culprit but there’s also no denying how the bowling of some teams-India, for example-has evolved drastically to deliver more results at home as well as away. Also factor in the reputation of hosts like South Africa where there hasn’t been a draw since 2016 and this sudden surge of results makes all the more sense.

This year not producing any draw plays perfectly to the cause the ICC has been promoting by way of a World Test Championship-that every Test match must be incentivised with a result to allow for a point-wise grading of teams. Further expediting it are foggy concepts like Bazball that haven’t allowed England to approach their tour of India with more nuance.

Not to forget, these results will only further strengthen the argument that Test cricket perhaps can do without the fifth day. The ICC officially started pushing for it in 2017 with a 98 overs per day four-day Test between South Africa and Zimbabwe at Port Elizabeth that finished within two days. But this recent spate of results shows four-day Tests could unofficially be the norm even if the playing conditions aren’t tinkered with.

Read more news like this on HindustanTimes.com