Alan Shearer’s statue is the best part of 100 miles from Alan Shearer Way. The former is famously just outside St James’ Park, a bronzed right arm up in trademark celebration which, it is to be hoped, he performed after all 206 of his goals for Newcastle United.

But the road named after Newcastle’s local hero is on the other side of the Pennines, a stretch of A666 that runs past Ewood Park as far as Shearer’s Island; which, it has to be said, is a rather grandiose name for a roundabout.

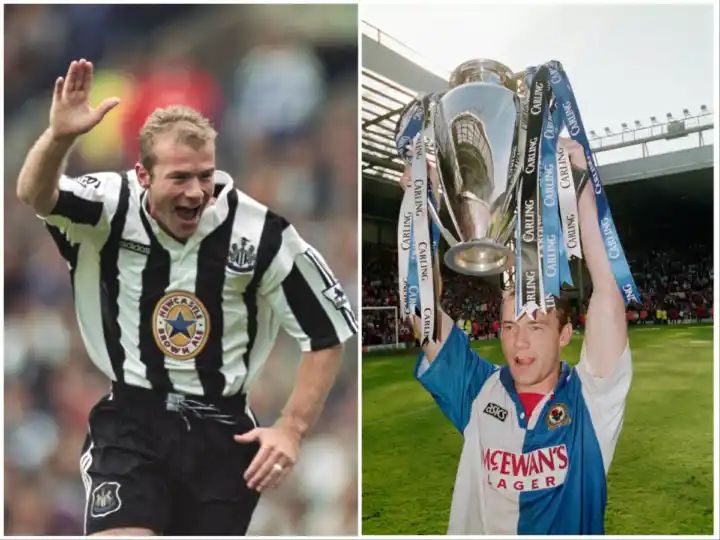

Blackburn Rovers against Newcastle is a meeting of six-time FA Cup winners, but when they have not triumphed since 1928 and 1955 respectively. It is also the Shearer derby, a clash of clubs united by their love for a prolific No 9. Shearer became Newcastle’s record goalscorer, dislodging another prolific Geordie, in Jackie Milburn. He made history of a different sort with Blackburn: not merely with his scoring feats, but by making them champions of England for the first time since World War 1.

When Rovers dropped into League One in 2017, they were a still more anomalous presence on the Premier League’s roll of honour. A traditional club, founders of the Football League, were ahead of their time in one respect, accused of buying the title, but while both they and Newcastle were big spenders in the 1990s, smashing transfer records – Blackburn the British and Newcastle the world – to sign Shearer, the expenditure came in a different context.

Blackburn’s was funded by Jack Walker, the Lancastrian steel magnate, Newcastle’s by Sir John Hall, the Northumbrian property developer who oversaw the construction of the Gateshead MetroCentre. All of which, with Blackburn still unhappily owned by the Indian chicken firm Venky’s and Newcastle’s recent spending funded by the Saudi Arabian Public Investment Fund, feels like another era.

In a different millennium, Shearer was a front man for ambitious teams and projects alike. Symbolically, he joined newly-promoted Blackburn in 1992: his career took off with the start of the Premier League.

He mustered 23 goals in 118 top-flight games for Southampton but has been the new division’s record scorer for virtually all of its existence, his tally of 260 looking safer as long as Harry Kane stays in Germany.

But, besides Walker’s largesse, with a new division, transfer fees mushroomed. Blackburn paid £3.3m for Shearer, which then seemed a colossal sum. His heavily pregnant wife was initially unimpressed. As they first drove around Blackburn, Shearer recounted last year, she said: “What the f**

* have you done?” And if, perhaps in different language, the same question was posed of Kenny Dalglish, Shearer’s success showed his manager had the financial acumen to accompany his footballing knowledge.

Dalglish was always defensive about his spending. “When considering whether to buy a player, I always thought of his resale value,” he wrote in his autobiography. Many of Dalglish’s deals made Rovers money and they pocketed a huge profit when selling Shearer to Newcastle for £15m four years later.

But there were three clubs in the relationship: Manchester United missed out on Shearer in 1992, expressing an interest but asking him to wait while Dalglish pounced. The striker met Sir Alex Ferguson in 1996. “At one point, I thought I was going to Manchester United,” Shearer said years later, but the allure of Tyneside proved too strong.